In this article, we will attempt to write an HTTP server from scratch on top of the TCP layer. However, to understand the logic of the process, we need to first delve into processes.

Processes running on the operating system need to communicate with each other. There are various methods that processes can use to communicate with each other. Shared Memory, Message Passing, and similar methods are commonly used for inter-process communication.

However, let’s consider that these two processes are running on different machines. In client-server systems like these, the most common methods for communication between processes are sockets, remote procedure calls (RPCs), and pipes.

However, let’s consider that these two processes are running on different machines. In client-server systems like these, the most common methods for communication between processes are sockets, remote procedure calls (RPCs), and pipes.

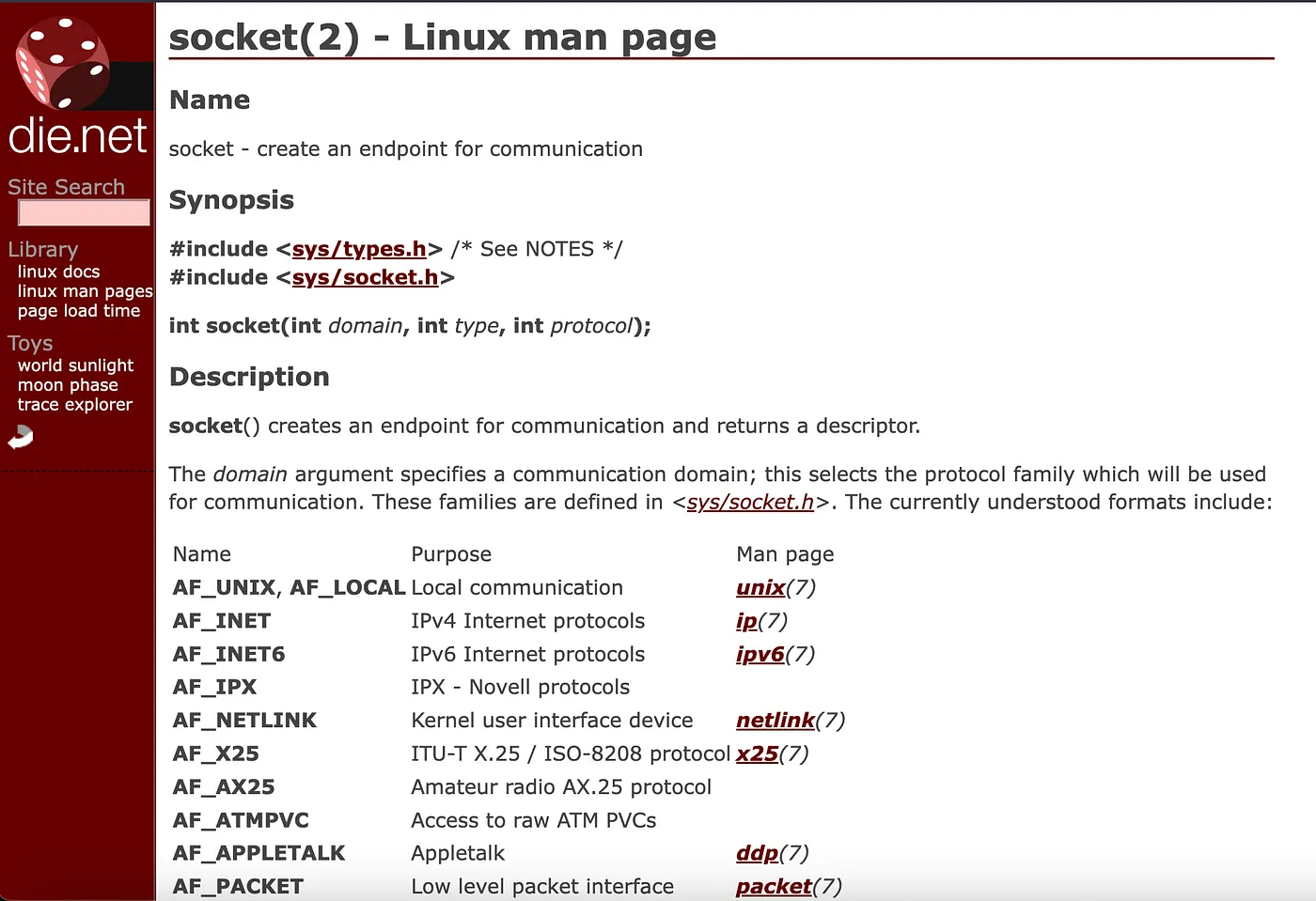

In this article, we will utilize communication using sockets. So, what is a socket? Sockets enable processes to communicate with each other over the network. Operating systems have different implementations for sockets. For detailed information about Linux’s socket implementation, for example, we can refer to the Linux Kernel documentation.

Various types of sockets exist, such as TCP sockets, UDP sockets, and others. The primary purpose of these sockets is to facilitate communication between processes running on the network over the network.

For instance, when two isolated processes, such as the application where you keep your notes and a grammar check application that verifies your writing rules, need to communicate, they can use TCP sockets to exchange information in a specific format.

In the same way, our server app process (backend) running on the server and the process (client) attempting to access it via a web browser will communicate fundamentally over TCP.

The HTTP protocol is a protocol built on top of TCP. So, what does the term ‘protocol’ mean? A protocol is a set of predefined rules that two systems follow when communicating with each other. Messages sent in a specific format according to the rules of HTTP are interpreted and necessary actions are taken by the other system that understands the language/rules.

Now, we can start writing our HTTP server from scratch. First, we will ask the operating system to set up a socket for us:

using System.Net.Sockets;

using var socket = new Socket(SocketType.Stream, ProtocolType.Tcp);When we run the above code on a Linux operating system, our code, through the GNU C Library (libc), makes a system call to the Linux kernel, and the kernel provides us with a TCP socket. (This can vary depending on the programming language used.)

Let’s continue from where we left off in the code. Since we will be using TCP for byte streaming, we specify that the socket is of type Stream. Additionally, we indicate that the protocol to be used is TCP. Now, we need to specify which host and port numbers to bind to this socket.

using System.Net;

using System.Net.Sockets;

using Socket socket = new Socket(SocketType.Stream, ProtocolType.Tcp);

var host = IPAddress.Parse("127.0.0.1");

var port = 7888;

var endpoint = new IPEndPoint(host, port);

socket.Bind(endpoint);This endpoint is composed of an IP address and a port number. The reason for using a port number is to determine which process on the machine will receive the transmitted message among many processes. The use of an IP address is to understand which machine on the network will receive the message. In the end, the endpoint used by TCP takes a structure like 127.0.0.1:5300.

As seen, we have bound the socket to the 7888 port on our local machine, identified by the address 127.0.0.1. Now, we can start listening on this endpoint.

using System.Net;

using System.Net.Sockets;

using Socket socket = new Socket(SocketType.Stream, ProtocolType.Tcp);

var host = IPAddress.Parse("127.0.0.1");

var port = 7888;

var endpoint = new IPEndPoint(host, port);

socket.Bind(endpoint);

socket.Listen(10);

Console.WriteLine($"Listening on port {port}...");

while (true)

{

// Accept incoming connection

Socket clientSocket = socket.Accept();

// Handle the accepted socket

HandleClient(clientSocket);

}

void HandleClient(Socket clientSocket)

{

// Handle the connection (you can add your logic here)

// For example, read data from the client

byte[] buffer = new byte[1024];

int bytesRead = clientSocket.Receive(buffer);

string receivedData = Encoding.ASCII.GetString(buffer, 0, bytesRead);

Console.WriteLine($"Received data: {receivedData}");

// Close the client socket

clientSocket.Close();

}The number 10 in the code specifies the backlog. So, what is the backlog? Multiple clients may want to connect to our server simultaneously. However, establishing the connection between the server and the client takes time due to the three-way handshake. In this case, incoming connection requests are queued up. The backlog parameter determines how many connections will be queued up in this queue. If more connection requests come in, our server will reject them.

Now, our socket is in a listening state. However, at the moment, it only prints the message sent by the client to the console. Now, let’s see what we will do with these packets coming over TCP, i.e., how we will write the HTTP server. In a sense, we will teach HTTP rules to TCP. For this, let’s take a closer look at HTTP first.

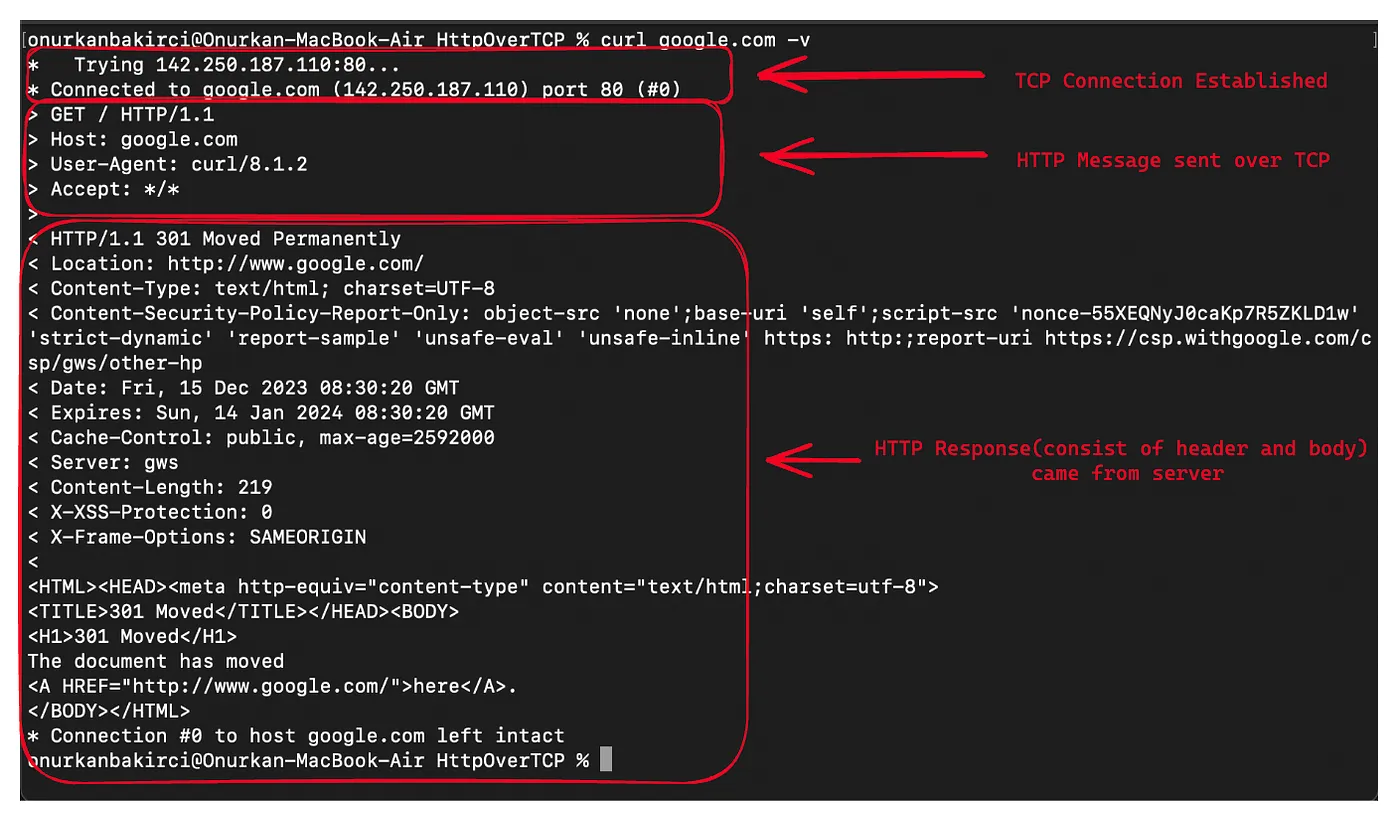

HTTP requests consist of two main parts: header and body. Below is a simple GET request sent to the google.com address.

As can be understood from the image, the steps involved are:

- Connect to the server via TCP connection.

- Send an HTTP message over the TCP connection.

- Read the response sent by the server.

- Close the connection.

So far, with the above code block, we have only written the part that establishes the TCP connection. Now, we need to interpret the incoming HTTP message in a specific format.

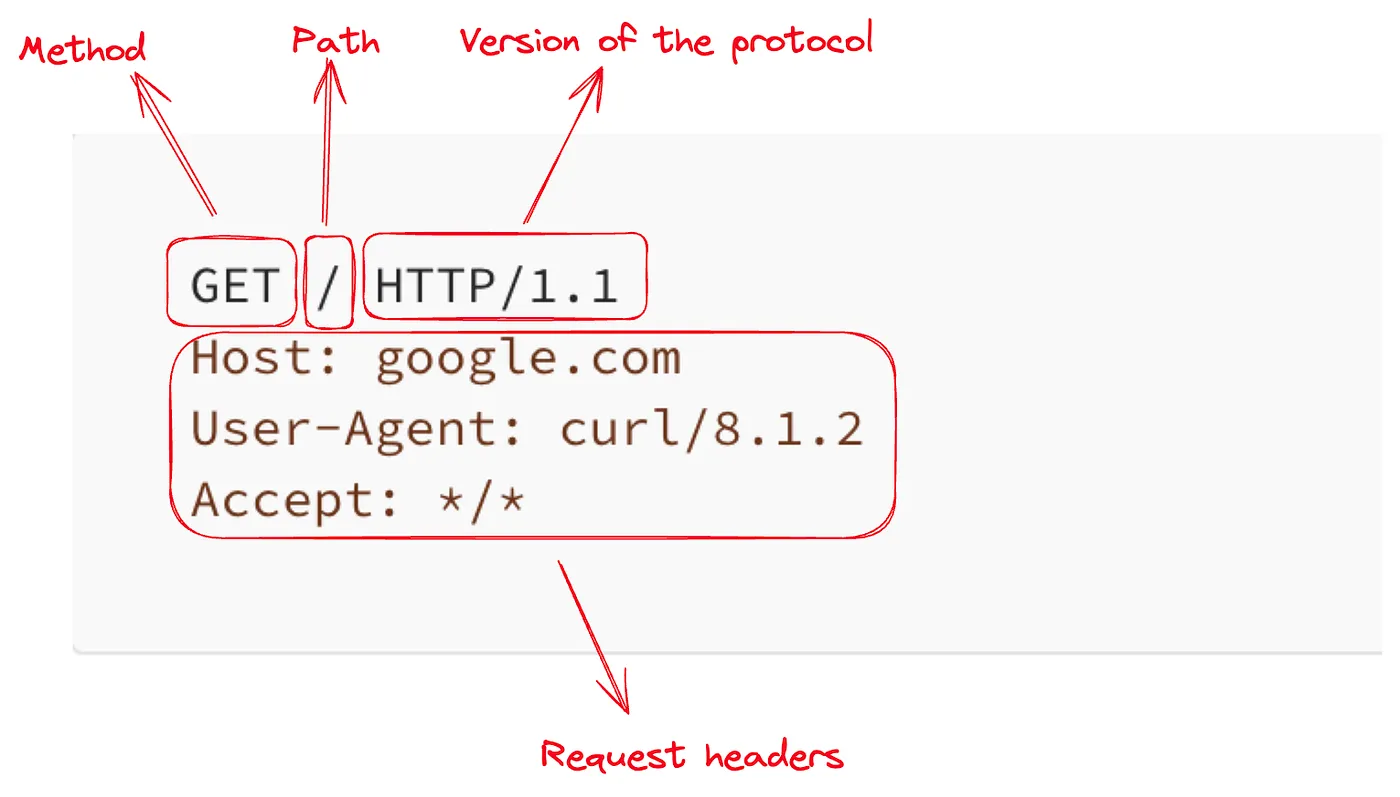

Accordingly, let’s take a closer look at the HTTP message sent by the client.

In addition to the image above, there is a special character \r\n at the end of each line. This represents a line break. Additionally, each empty line between lines indicates a new segment. For example, the empty line between the HTTP response header and the response body distinguishes these two parts.

We need to parse this incoming HTTP request on our TCP server. We can do this as follows:

void HandleClient(Socket clientSocket)

{

// Handle the connection (you can add your logic here)

// For example, read data from the client

byte[] buffer = new byte[1024];

int bytesRead = clientSocket.Receive(buffer);

string receivedData = Encoding.ASCII.GetString(buffer, 0, bytesRead);

Console.WriteLine($"Received data: {receivedData}");

string[] lines = receivedData.Split("\r\n"); // Split all lines by new line

string[] requestLine = lines[0].Split(' '); // Split the first line by space

string method = requestLine[0]; // GET, POST, PUT, DELETE, etc.

string path = requestLine[1]; // The path of the request like /index.html

string httpVersion = requestLine[2]; // HTTP version like HTTP/1.1

// ...

// handle the request based on the method and path

// by using backend application server logic

// ...

// Send a simple HTTP response back to the client

string response = "HTTP/1.1 200 OK\r\nContent-Type: text/plain\r\n\r\nHello, World!";

byte[] responseBytes = Encoding.ASCII.GetBytes(response);

clientSocket.Send(responseBytes);

// Close the client socket

clientSocket.Close();

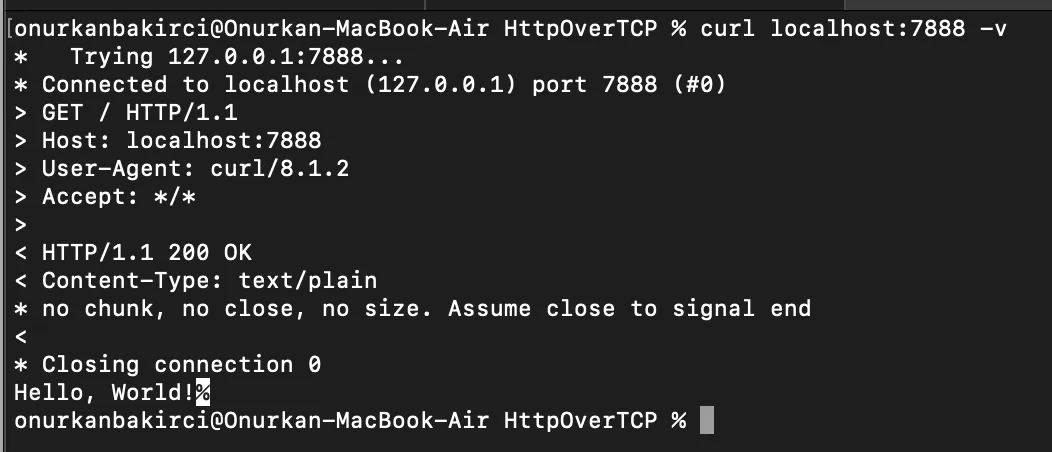

}Here, we are parsing the incoming request according to HTTP standards. Later, based on the content of this parsed HTTP request, we enable our backend application to perform its logic. Finally, we create a response and send it back to the client as bytes.

By following this approach, we have essentially written a basic HTTP server. The server we’ve created can be further developed into a real HTTP server. For this, the implementation of all HTTP standards is required. We can refer to the RFC pages for the HTTP standards. For example, to explore the details of the HTTP 1.0 implementation, you can visit this link.

Finally, let’s take a look at HTTP versions and the features they bring. HTTP is developed by the HTTP community and is becoming more efficient over time. Briefly looking at its history:

- HTTP 0.9: The first version of HTTP, performing basic request/response operations at a simple level.

- HTTP 1.0: Introduced new features such as status codes, request/response headers.

- HTTP 1.1: This version introduced the pipelining feature, eliminating the need to wait for the response of a previous request before sending a new one. This allowed sending multiple requests in succession, increasing speed. It also introduced the ability to reuse the same connection for other requests.

- HTTP 2.0: In previous HTTP versions, a new connection was opened for each request. With HTTP 1.1, the ability to send multiple parallel requests over a single connection (multiplexing) was introduced.

- HTTP 3.0: Started using QUIC instead of TCP in the transport layer.

You can access the GitHub code from the link.